By Rose L. Thayer/Stars and Stripes

Robert Stillman Garcia- laid to rest after being identified eight days after being killed while serving on the USS California.

Robert Stillman Garcia may have gone missing in action during the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, but his legacy of service held strong in his family during the eight decades it took for him to return home.

“I never thought this day would come,” said Navy Lt. Allison Ledesma, his great grand niece.

She knew Garcia primarily from the portrait of him that hung in her childhood living room alongside the telegram informing the family he was missing. Garcia was 23 and serving as storekeeper 3rd class on the USS California — his first duty assignment — when the Japanese attacked.

He was assumed to be among the nearly 2,400 Americans killed that day, but the Navy did not confirm the identity of his remains until six months ago.

When Ledesma arrived at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 75 years after him, it was also as her first duty station. She felt the family legacy the moment she saw Garcia’s name on the California’s memorial.

“Seeing his name there made it real for me,” she said. “I have this personal connection.”

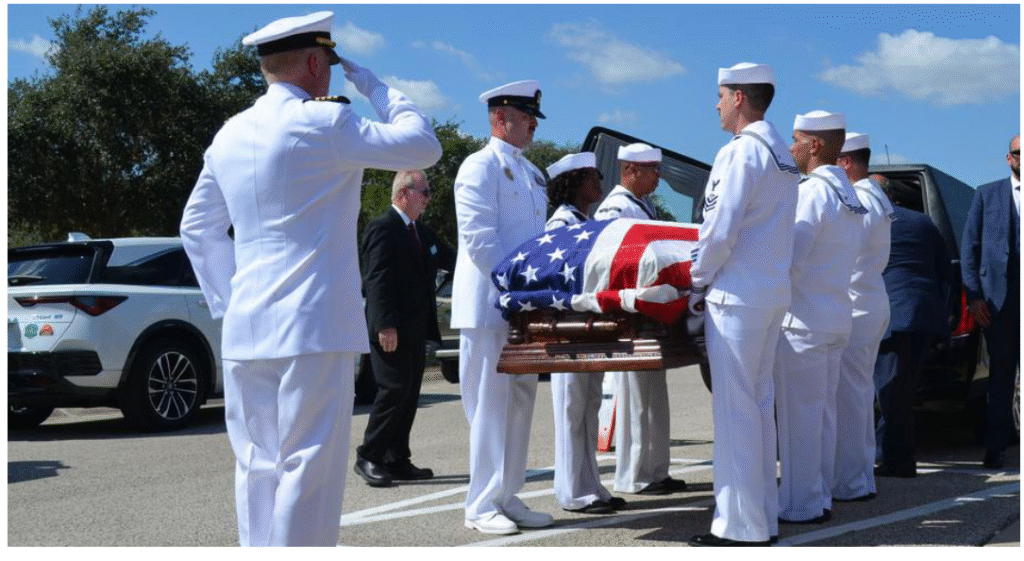

Ledesma spoke of her Tio Beto’s legacy Tuesday following a burial service at the Coastal Bend State Veterans Cemetery in Corpus Christi, where hundreds of family and community members gathered to pay respects on an unseasonably hot afternoon.

Thanks to a renewed effort in 2018 to identify sailors lost on the California, Garcia’s remains were confirmed in April.

JR Bonilla, a Marine Corps veteran and great grand nephew of Garcia, accepted a folded American flag during the service on behalf of his family.

“The closer we got to today’s service, the more real it has gotten,” he said.

Garcia was born on Jan. 3, 1918, in Concepcion, a tiny town 85 miles southwest of Corpus Christi, and enlisted at age 22, according to the Navy. After basic training in San Diego, he arrived in Hawaii and joined the crew of the California in October 1940.

He stayed in touch with his family — eventually asking his older sister Sara G. Canales to stop sending so many cookies and cakes because it was causing too much attention with his shipmates, said David Valadez, a great nephew of Garcia who now holds the correspondence between the siblings. Instead, Garcia asked his sister to save the baking for when he visited home soon.

After the attack on Dec. 7, 1941, many of those shipmates began writing to the family that Garcia was thought to be alive. But as the months dragged on, it became clear he was missing in action.

In total, 102 crew members from the California were killed. The remains of 42 sailors and Marines were identified immediately and were buried at the Halawa Naval Cemetery and Nuuanu Cemetery

The crew had been preparing for an inspection that morning, so many of the watertight doors, portholes and exterior doors were open. The Tennessee-class battleship took two torpedo hits about 8:05 a.m., piercing the hull and rupturing the forward fuel tanks. It rapidly flooded and listed to port.

The ship’s 5-inch guns and two of its .50-caliber machine guns were fired in response, but the crew quickly ran out of ammunition. The California then sustained multiple bomb hits that ignited a fire that destroyed the structural integrity of the battleship. Over the next three days, it continued to fill with water and sank to the seafloor.

Salvage efforts remained ongoing, and the California was refloated on March 24, 1942. The crew members who could not be identified were buried as unknowns at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

In 1947, American Graves Registration Service personnel disinterred the unknowns for further analysis, resulting in 39 additional identifications, according to the Defense POW/MIA Agency.

Identification efforts renewed in 2018, when DPAA exhumed the final missing sailors of the California, which has resulted in 11 identifications. Nine of Garcia’s shipmates remain unidentified, according to DPAA.

Ledesma’s grandmother was among three family members to submit DNA to the Navy, which helped return Garcia home. Because Ledesma is now on a second tour at Pearl Harbor, she was involved in the process with DPAA, including serving as the official escort to bring her great uncle home to Texas.

“Part of him will always remain in Pearl Harbor,” she said. “Part of him gets to be home.”